The following article serves as an terrifyingly poignant microcosm of the entire U.S. economy. It also contains language and practices that are right out of the subprime mortgage industry, which catalyzed the financial collapse of 2008.

The following article serves as an terrifyingly poignant microcosm of the entire U.S. economy. It also contains language and practices that are right out of the subprime mortgage industry, which catalyzed the financial collapse of 2008.

The piece starts off by relaying the story of law professor, David Frakt, who was forcibly removed while in the middle of a speech at the Florida Coastal School of Law, for telling the faculty and staff the truth about the “for-profit” law school’s flawed and unethical business model.

For its private equity owners; however, it is the perfect “investment.” With unlimited federal funds available for graduate school loans, they take the money in now with little risk. As such, they simply accept almost anyone who applies, whether or not they are actually qualified to practice law (a large percentage are demonstrably not). For the law school students saddled with debt, and the taxpayer backing these loans, it’s not such a good deal. Crony Capitalism 101 wins again.

Rather than express more of my thoughts here, I’ll provide perspective within the excerpts of the article itself, which is quite lengthy.

From The Atlantic:

But midway through Frakt’s statistics-filled PowerPoint presentation, he was interrupted when Dennis Stone, the school’s president, entered the room. (Stone had been alerted to Frakt’s comments by e-mails and texts from faculty members in the room.) Stone told Frakt to stop “insulting” the faculty, and asked him to leave. Startled, Frakt requested that anyone in the room who felt insulted raise his or her hand. When no one did, he attempted to resume his presentation. But Stone told him that if he didn’t leave the premises immediately, security would be called. Frakt packed up his belongings and left.

What had happened? Florida Coastal is a for-profit law school, and in his presentation to its faculty, Frakt had catalogued disturbing trends in the world of for-profit legal education. This world is one in which schools accredited by the American Bar Association admit large numbers of severely underqualified students; these students in turn take out hundreds of millions of dollars in loans annually, much of which they will never be able to repay. Eventually, federal taxpayers will be stuck with the tab, even as the schools themselves continue to reap enormous profits.

Florida Coastal is one of three law schools owned by the InfiLaw System, a corporate entity created in 2004 by Sterling Partners, a Chicago-based private-equity firm. InfiLaw purchased Florida Coastal in 2004, and then established Arizona Summit Law School (originally known as Phoenix School of Law) in 2005 and Charlotte School of Law in 2006.

These investments were made around the same time that a set of changes in federal loan programs for financing graduate and professional education made for-profit law schools tempting opportunities. Perhaps the most important such change was an extension, in 2006, of the Federal DirectPLUS Loan program, which allowed any graduate student admitted to an accredited program to borrow the full cost of attendance—tuition plus living expenses, less any other aid—directly from the federal government. The most striking feature of the Direct PLUS Loan program is that it limits neither the amount that a school can charge for attendance nor the amount that can be borrowed in federal loans. Moreover, there is little oversight on the part of the lender—in effect, federal taxpayers—regarding whether the students taking out these loans have any reasonable prospect of ever paying them back.

This is, for a private-equity firm, a remarkably attractive arrangement: the investors get their money up front, in the form of the tuition paid for by student loans. Meanwhile, any subsequent default on those loans is somebody else’s problem—in this case, the federal government’s. The arrangement bears a notable resemblance to the subprime-mortgage-lending industry of a decade ago, with private equity playing the role of the investment banks, underqualified law students serving as the equivalent of overleveraged home buyers, and the American Bar Association standing in for the feckless ratings agencies. But there is a crucial difference. When the subprime market collapsed, legislation dedicating hundreds of billions of taxpayer dollars to bailing out the banks had to be passed. In this case, no such action will be necessary: the private investors have, as it were, been bailed out before the fact by our federal educational-loan system. This situation, from the perspective of Sterling Partners and other investors in higher education, comes remarkably close to the capitalist dream of privatizing profits while socializing losses.

From the perspective of graduates who can’t pay back their loans, however, this dream is very much a nightmare. Indeed, it’s easy to make the case that these students wind up in far worse shape than defaulting homeowners do, thanks to two other differences between subprime mortgages and educational loans. First, educational debt, unlike mortgages, can almost never be discharged in bankruptcy, and will continue to follow borrowers throughout their adult lives. And second, mortgages are collateralized by an asset—that is, a house—that usually retains significant value. By contrast, anecdotal evidence suggests that many law degrees that do not lead to legal careers have a negative value, because most employers outside the legal profession don’t like to hire failed lawyers.

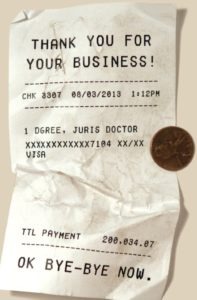

How much debt do graduates of the three InfiLaw schools incur? The numbers are startling. According to data from the schools themselves, more than 90 percent of the 1,191 students who graduated from InfiLaw schools in 2013 carried educational debt, with a median amount, by my calculation, of approximately $204,000, when accounting for interest accrued within six months of graduation—meaning that a single year’s graduating class from these three schools was likely carrying about a quarter of a billion dollars of high-interest, non-dischargeable, taxpayer-backed debt.

And what sort of employment outcomes are these staggering debt totals producing? According to mandatory reports that the schools filed with the ABA, of those 1,191 InfiLaw graduates, 270—nearly one-quarter—were unemployed in February of this year, nine months after graduation. And even this figure is, as a practical matter, an understatement: approximately one in eight of their putatively employed graduates were in temporary jobs created by the schools and usually funded by tuition from current students. InfiLaw is not alone in this practice: many law schools design the brief tenure of such “jobs” to coincide precisely with the ABA’s nine-month employment-status reporting deadline. In essence, the schools are requiring current students to fund temporary jobs for new graduates in order to produce deceptive employment rates that will entice potential future students to enroll. (InfiLaw argues that these jobs have “proven to be an effective springboard for unemployed graduates to gain experience and secure long-term employment.”)

I don’t know about you, but to me, this sounds pretty much like the definition of a ponzi scheme.

Among students who graduated from InfiLaw schools in 2013, for instance, the percentage who obtained federal clerkships or jobs with large law firms was slightly below 1 percent—0.92 percent, to be exact. In other words, the odds of a graduate of one of these schools getting a job that arguably justifies incurring the schools’ typical debt level are essentially 100 to 1.

Over the next few years, the InfiLaw schools did their best to obtain as much of that revenue as possible. Florida Coastal, which had existed for eight years prior to its purchase by InfiLaw, nearly doubled in size, growing from 904 students in 2004 to 1,741 in 2010. Phoenix—now Arizona Summit—grew at a still faster rate, increasing from 336 students in 2008 to 1,092 just four years later. Charlotte likewise expanded, from 481 students in 2009 to 1,151 in 2011. Despite across-the-board declines for the past few years, all three schools remain among the largest law schools in the country.

The InfiLaw schools achieved this massive growth by taking large numbers of students that almost no other ABA-accredited law school would consider admitting. InfiLaw was—and remains—up-front about this. Its self-described mission is to “establish the benchmark of inclusive excellence in professional education,” by providing access to a traditionally underserved population consisting “in large part of persons from historically disadvantaged groups.” Yet this means accepting many students who, given their low LSAT scores, are unlikely to ever have successful legal careers. And it is worth noting that a large number of those who take the LSAT do not end up enrolling in law school. (InfiLaw says it does not rely as heavily on the LSAT as other schools do, because “it is not the best determinant of success as a lawyer and clearly has racial bias.” The company says it has instead developed a tool that is “demonstrably superior to the LSAT.” Called the AAMPLE program, it involves applicants’ passing two classes prior to admission.)

Didn’t we hear these exact arguments in favor of pushing home ownership on people who couldn’t afford it?

The InfiLaw schools’ rapid expansion was greatly aided by the fact that, until two years ago, the vast majority of law schools published essentially no meaningful employment information. Schools reported “employment rates” that included everything from a six-figure post at a large firm to a part-time job at Starbucks. They revealed little or nothing about what percentage of their graduates were working as lawyers, let alone what salaries they were earning.

The drop-off in applications hit the InfiLaw schools hard. In total, the three schools received 12,754 applications in 2010; three years later that total had fallen by 37 percent, to 8,066. At Florida Coastal the decline was particularly severe, with applications falling by more than half. In his presentation to the faculty, Frakt made clear that the school’s administration—by which he meant the management of InfiLaw, and ultimately that of Sterling Partners—had reacted by drastically cutting the school’s already very low admissions standards.

Florida Coastal’s 2013 entering class had a median LSAT score of 144, which was in the 23rd percentile of all test-takers. Fully a quarter of the class had a score of 141 or lower, which meant that they scored among the bottom 15 percent of test-takers. (The entering classes of Charlotte and Arizona Summit had identical median and bottom-quarter LSAT scores, suggesting that these numbers were chosen somewhere high up on the corporate ladder.)

Lawyers may be notoriously bad at math, but this equation was simple enough. The ABA requires schools to maintain certain bar-passage rates, or they risk losing their accreditation. Indeed, the ABA’s standards state that “a law school shall not admit applicants who do not appear capable of … being admitted to the bar.” By admitting so many students who, upon graduation, seemed unlikely ever to pass the bar, Frakt pointed out, Florida Coastal was running a serious risk of being put on probation and eventually de-accredited, which would put the school in a financial death spiral. (A loss of accreditation would make it impossible for students to receive federal loans and, crucially, would prevent students from taking the bar exam in many states.)

So why has InfiLaw—or, more accurately, Sterling Partners—gone down this route? A Florida Coastal faculty member who is familiar with the business strategies of private-equity firms told me that, in his view, the entire InfiLaw venture was quite possibly based on a very-short-term investment perspective: the idea was to make as much money as the company could as fast as possible, and then dump the whole operation onto someone else when managing it became less profitable.

It is important to note that while InfiLaw’s abuse of the student-loan system may be egregious, it is far from unique. Ultimately, this story is about not only for-profit law schools, or law schools, or even for-profit higher education. It is about the problematic financial structure of higher education in America today. It would be comforting to think that the crisis is confined to for-profit schools—and indeed this idea is floated regularly by defenders of higher education’s status quo. But it would be more accurate to say that for-profit schools, with their unabashed pursuit of money at the expense of their students’ long-term futures, merely throw this crisis into particularly sharp relief. To see why, consider the regulatory and political mechanisms that have allowed InfiLaw to make such handsome profits while producing disastrous results for so many of its “customers.”

This is exactly what is happening throughout the entire U.S. economy. Success is irrelevant when it comes to policy decisions. Outcomes simply do not matter. All that matters is a small group of insiders must be able to thieve in the interim. How else could three of the worst law schools in the country be amongst the nation’s largest? How else does Timothy Geithner get appointed Treasury Secretary after being head of the New York Federal Reserve in the run up to the financial crisis (read: Matt Stoller Destroys Timothy Geithner in His Epic Review of “Stress Test”).

It’s all the same trade. The entire U.S. economy revolves around a small and unaccountable group of insiders gaming the system to earn risk-less profits, while damaging the overall economy and their so-called “customers” (whether the customers are law students, or citizens in general). This is why the public is so upset.

The only real difference between for-profit and nonprofit schools is that while for-profits are run for the benefit of their owners, nonprofits are run for the benefit of the most-powerful stakeholders within those institutions.

Consider the case of New England Law, a school of modest academic reputation that for many years produced a reasonable number of local practitioners at a non-exorbitant price. Like many similar schools, New England Law has spent years jacking up tuition and fees by leaps and bounds—after nearly doubling its price tag between 2004 and 2014, the school now costs about $44,000 a year—and graduating invariably large classes, even as the demand for legal services, and especially the legal services of graduates of low-ranked law schools, has contracted radically.

A glance at New England Law’s tax forms suggests who may have benefited most from this trajectory: John F. O’Brien, the school’s dean for the past 26 years, whom the school paid more than $873,000 in its 2012 fiscal year, the most recent yet disclosed. This is among the largest salaries of any law-school dean in the country. (By comparison, the dean at the University of Michigan Law School, a perennial top-10 institution, was reported to make less than half as much, $420,000, in 2013.) Meanwhile, the school’s graduates are burdened with crushing debt loads and job prospects only marginally less terrible than those of InfiLaw graduates. Approximately 41 percent of the students in New England Law’s 2013 graduating class had jobs as lawyers nine months after graduation, and nearly 20 percent were unemployed. (Patrick Collins, a spokesman for New England Law, said in an e-mail that, while the school does not publicly discuss its employees’ salary amounts, O’Brien “has voluntarily reduced his salary by more than 25 percent.” Collins also noted that, among last year’s employment statistics for the eight law schools in Massachusetts, New England Law’s ranked “in the middle” in terms of graduates who were “employed in full-time, long-term, JD-required positions within nine months of graduation.”)

O’Brien’s résumé reveals that he has served recently as the chair of both the Council of the Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, which oversees the ABA’s accreditation standards, and of the Section’s Accreditation Committee. In short, a better example of what economists and political scientists refer to as “regulatory capture”—the takeover of administrative oversight mechanisms by the very interests those mechanisms are supposed to be regulating—would be hard to find.

None of this is to claim that greed and other selfish motivations are the only—or even the principal—drivers of the problematic trends in American higher education. Across the ideological spectrum, it is almost universally assumed that more and better education will function as a panacea for un- and underemployment, slow economic growth, and increasingly radical wealth disparities. Hence the broad support among liberal, moderate, and conservative politicians alike for the goal of constantly increasing the percentage of the American population that goes to college. Behind that support seems to lurk an inchoate faith—one that is absurd when articulated clearly, which is why it almost never is—that higher education will eventually make everyone middle-class.

More flashbacks to subprime and the belief that everyone needed to own a home, whether they could afford it or not.

This past April, the Congressional Budget Office projected that Americans will incur nearly $1.3 trillion in student debt over the next 11 years. That figure is in addition to the more than $1 trillion of such debt that remains outstanding today. This is the inevitable consequence of an interwoven set of largely unchallenged assumptions: the idea that a college degree—and increasingly, thanks to rampant credential inflation, a graduate degree—should serve as a kind of minimum entrance requirement into the shrinking American middle class; the widespread belief that educational debt is always “good” debt; the related belief that the higher earnings of degreed workers are wholly caused by higher education, as opposed to being significantly correlated with it; the presumption that unlimited federal loan money should finance these beliefs; and the quiet acceptance of the reckless spending within the academy that all this money has entailed. These assumptions enabled InfiLaw’s lucrative foray into the world of for-profit education. But they have just as surely shaped the behavior of nonprofit colleges and universities.

Hey, but at least private equity gets paid. Amirite?

Donate bitcoins: 35DBUbbAQHTqbDaAc5mAaN6BqwA2AxuE7G

Follow me on Twitter.

Well, I guess the joke is on them, since those millions of dollars they screwed out of us taxpayers are being rapidly inflated into valuelessness.

No, I’d say the joke is definitely on us. They can buy all sorts of nice things with that cash.

You can only be smug about people playing Old Maid if you’ve already moved into alternatives.

Well, check out what Harvard Law is doing with their graduates… Medicine is even more sickeningly unaffordable. Young docs & increasingly nursing & PA students as well will be locked in perpetual government servitude by their debt. I tell all young people to go to med school in Southern Europe , Poland or the islands. India also a reasonable place to get educated. The theft of the future by my generation is disgusting.

Excellent blog! A good website (with over 3M views) that has been dealing in a very straightforward way the law school scam, is named Third Tier Reality.

But you can imagine that some will actually get work as police, and since they have a “degree” they’ll be issued more important roles. Scary.

Off topic: But I’ve noticed nowadays many kids pretending to actually know something because they have a “degree.” They actual believe that data and statistics are definitive and if you question them on it then you get “I’m a science major!”

So now we live in a society filled with cheap, abundant and useless higher education, and a bunch of overzealous brats that, not only bought into the sham, but parade it around like they’ve been anointed by it.

Science isn’t useless.

You are talking about people seduced by historicism or scientism, who misapply the methods of the physical sciences in contexts where they aren’t valid, like psychology or economics.

Read more:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Poverty_of_Historicism

This kind of thing is precisely why Thomas Jefferson considered the jury system the final bulwark for liberty; because the jury has the power to decide the law in question stinks, and we don’t give a shit what the guy did; “not guilty.”

The good news is that recent graduates ready to risk their new legal career on pro-bono work can start suing them for practice.

law school and graduate education in america has become a scam. almost entirely.

any money flow that can be exploited will be. those that appear ‘legitimate’ tend to be larger more reliable and politically defensible flows—–so the money keeps flowing backed by confetti printing.

i work in a big law firm. there is not a thought or care in the world for ANYTHING OTHER THAN THE BIG BANK CLIENTS WHO PAY THE BILLS.

the structure of private/public legal beauracracy in america is meant to suck as much money out of the economic systems of the u.s. and the world at large (derived from imf banking) .

this ship sails only in one direction , and sinks if it turns around.

there is no benefit in killing the lawyers—only attempting to sabotage their clients. once the banks are gone, the lawyers will retreat to their caverns. some may even have to find a new method of making a living—the younger ones with obligations.